When your immune system turns on your own blood vessels, things go wrong fast. Vasculitis isn’t just a rash or a bad ache-it’s your body attacking the very pipes that carry blood to your organs. This isn’t rare, but it’s often missed because the symptoms look like the flu, arthritis, or even a sinus infection. By the time it’s caught, damage might already be done. The good news? If you know what to look for, and get the right care early, most people can live well with it.

What Exactly Is Vasculitis?

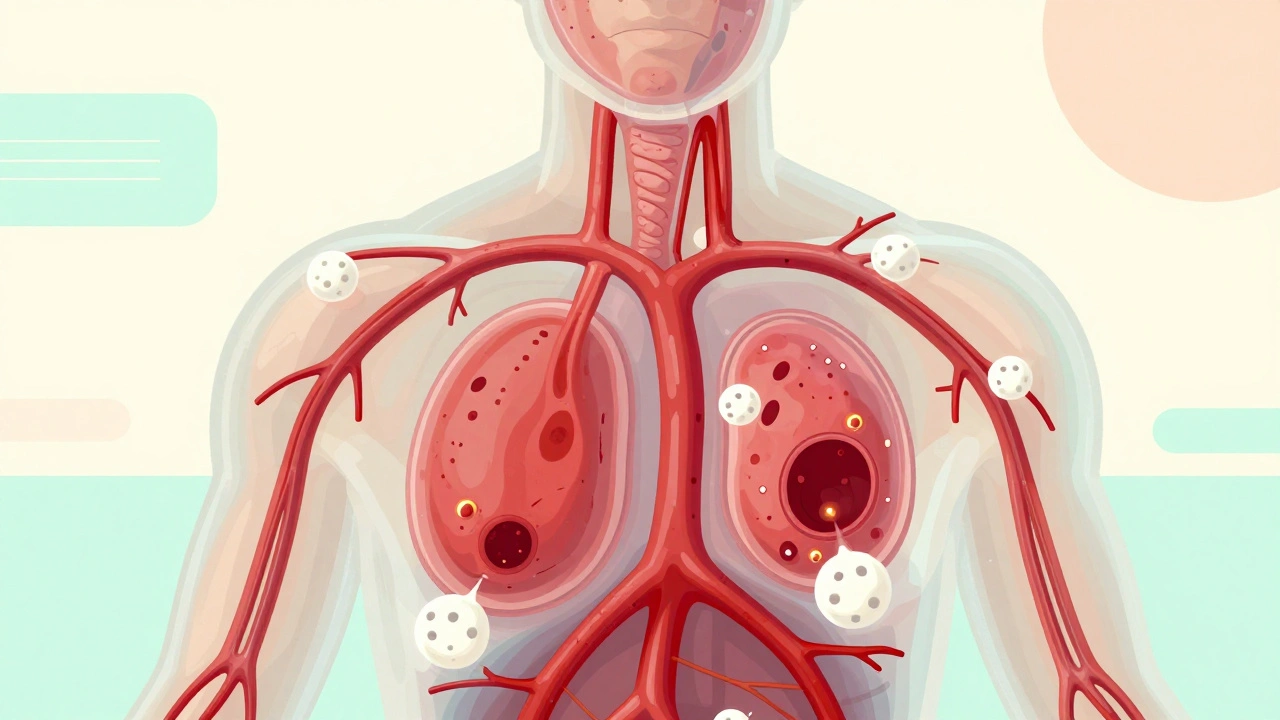

Vasculitis means inflammation of your blood vessels. That’s it. But that simple definition hides how dangerous it can be. When the walls of arteries, veins, or capillaries swell, they narrow. Blood flow slows. Sometimes, the vessel closes completely. Other times, it weakens and bulges into an aneurysm. Either way, the tissue downstream-your kidney, your nerve, your lung-starves for oxygen. That’s when organ damage starts. It’s autoimmune, which means your immune system, confused or overactive, mistakes your vessel walls for invaders. It’s not caused by infection or injury. It’s not contagious. It’s not your fault. And it’s not one disease-it’s a group of more than 20 different conditions, each with its own pattern, severity, and treatment. Doctors group them by the size of the vessels they hit:- Large-vessel vasculitis: Affects the aorta and its biggest branches. Think giant cell arteritis (GCA), which hits arteries in the head, especially in people over 50. It can cause headaches, jaw pain when chewing, and even sudden vision loss.

- Medium-vessel vasculitis: Targets medium-sized arteries. Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) and Kawasaki disease fall here. Kawasaki is mostly in kids under 5 and can cause coronary artery aneurysms if not treated fast.

- Small-vessel vasculitis: Hits the tiniest vessels-capillaries, venules. This includes the ANCA-associated types: granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA). These often affect kidneys, lungs, and nerves.

What Are the Warning Signs?

There’s no single symptom. Vasculitis wears many masks. That’s why it takes, on average, 6 to 12 months to get diagnosed. People see multiple doctors before someone connects the dots. Common signs include:- Red or purple spots, bumps, or bruises on the skin-especially on the legs

- Joint pain or swelling that doesn’t go away

- Chronic fatigue, fever, or weight loss without reason

- Numbness, tingling, or weakness in hands or feet

- Shortness of breath or coughing up blood

- Stomach pain, diarrhea, or bloody stools

- Headaches, vision changes, or scalp tenderness (especially if you’re over 50)

How Is It Diagnosed?

There’s no single blood test for vasculitis. Diagnosis is a puzzle. Doctors piece it together using four things: your symptoms, lab tests, imaging, and biopsy. Blood tests often show high inflammation:- ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) over 50 mm/hr

- CRP (C-reactive protein) above 5 mg/dL

How Is It Treated?

Treatment isn’t one-size-fits-all. It depends on the type, how bad it is, and which organs are at risk. The goal? Stop the immune attack, protect organs, and avoid long-term damage. For most severe cases, treatment starts with high-dose steroids like prednisone-often 0.5 to 1 mg per kg of body weight daily. But steroids alone aren’t enough. They’re like putting a bandage on a gunshot wound. You need something stronger to calm the immune system. That’s where immunosuppressants come in:- Cyclophosphamide: Used for severe ANCA vasculitis. Powerful, but has long-term risks like bladder damage and infertility.

- Rituximab: Targets B-cells. Now often preferred over cyclophosphamide because it’s just as effective with fewer side effects.

- Methotrexate or azathioprine: Used for maintenance after remission. You’ll take these for 18 to 24 months to keep the disease quiet.

What’s the Long-Term Outlook?

The good news? Most people go into remission. Around 80-90% of those with ANCA-associated vasculitis do. The bad news? Half of them will relapse within five years. That’s why lifelong monitoring is key. Your risk of serious complications depends on which organs are involved. The Five Factor Score helps predict survival:- No major organ damage? 95% five-year survival.

- One major organ affected (kidney, heart, GI)? Drops to 75%.

- Two or more? Falls to 50%.

Write a comment