When a patient needs an IV drip of normal saline, a life-saving chemotherapy shot, or a critical anesthetic before surgery, they expect it to be there. But in hospitals across the U.S., that expectation is increasingly unmet. As of July 2025, injectable medication shortages are affecting more than 220 drugs - and hospital pharmacies are feeling the pinch harder than anywhere else.

Why Hospitals Are Ground Zero

Retail pharmacies can swap out a pill for a similar one. They can tell a patient to come back next week. Hospitals can’t. Patients in ICU beds, emergency rooms, and operating theaters don’t have the luxury of waiting. Injectable drugs - the kind given through veins, muscles, or spinal taps - are the backbone of acute care. And they’re the most fragile part of the drug supply chain. About 60% of all active drug shortages involve sterile injectables. Why? Because making them is hard. These drugs must be produced in ultra-clean rooms, with no bacteria, no dust, no errors. One tiny mistake can wipe out a whole batch. And if a factory in India or China has a quality issue - like the one that shut down cisplatin production in February 2024 - the entire U.S. supply can vanish overnight. Unlike pills, injectables can’t be easily substituted. A different antibiotic might not work the same way. A different anesthetic could mean the difference between a smooth surgery and a cardiac arrest. That’s why hospital pharmacists spend an average of 11.7 hours a week just trying to find alternatives, call suppliers, and get approvals from pharmacy committees. That’s not time spent counseling patients or checking for interactions. That’s time spent firefighting.The Numbers Don’t Lie

Hospital pharmacies report that 35 to 40% of their essential inventory is affected by shortages. That’s more than triple the rate in community pharmacies. And it’s not random. The worst-hit categories are the ones you’d expect to be bulletproof:- Anesthetics: 87% in shortage

- Chemotherapeutics: 76% in shortage

- Cardiovascular injectables: 68% in shortage

Who’s Behind the Shortages?

It’s not one villain. It’s a web of broken incentives. Most injectable drugs are generics. That means they’re cheap. Manufacturers make only 3 to 5% profit on them. When a factory has to upgrade equipment, hire more inspectors, or rebuild after a tornado - like the one that hit Pfizer’s North Carolina plant in 2023 - they can’t afford it. Why spend $20 million to fix a machine that only makes $2 million a year in profit? Then there’s geography. Eighty percent of the raw ingredients for these drugs come from China and India. One flood, one political dispute, one FDA inspection failure - and the whole supply chain stumbles. The U.S. has no real backup. There’s no “Made in America” fallback for most of these drugs. Even when the FDA finds a problem - say, mold in a batch of epinephrine - they can’t force a company to fix it fast. The agency has limited power. Only 14% of shortage notifications lead to timely fixes. And the laws meant to help - like the 2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act - have done almost nothing. A government audit found they cut shortage duration by just 7%.

What Hospitals Are Doing to Survive

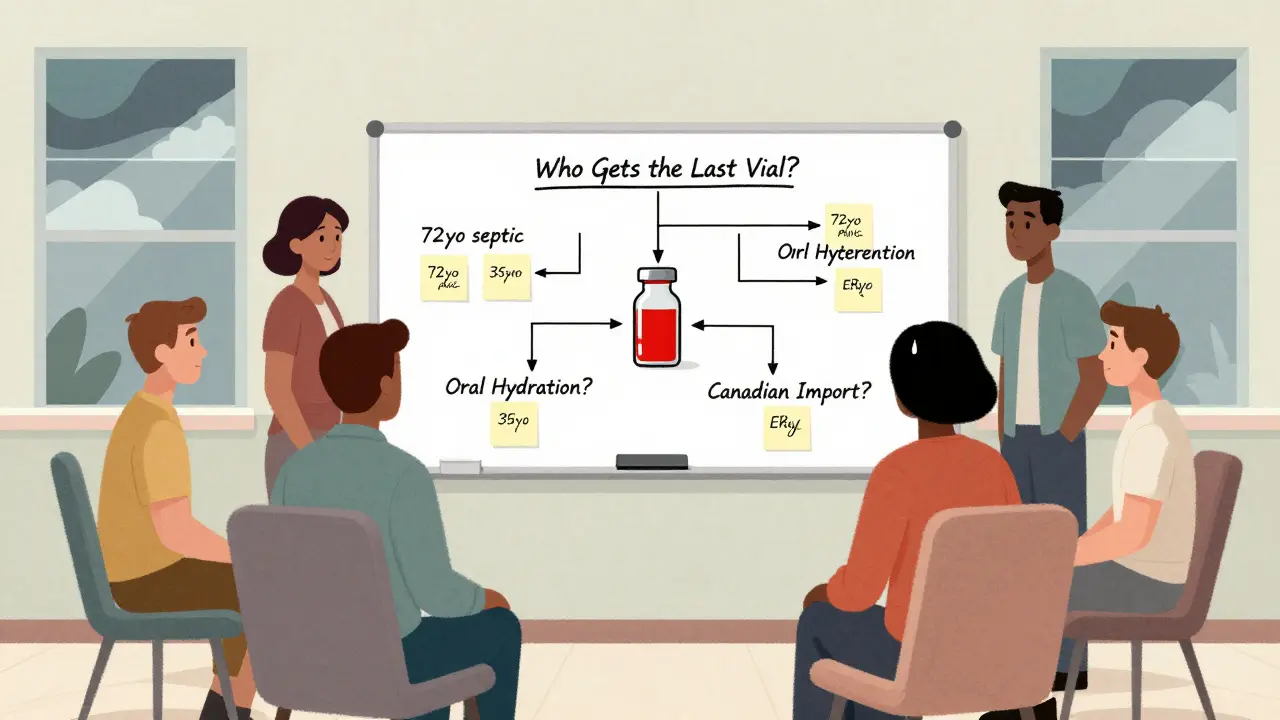

No one’s waiting for Washington to fix this. Hospital pharmacies are building their own lifelines. They’re forming shortage management teams - 76% of hospitals now have them. But only 32% feel those teams have enough staff, budget, or authority to make a real difference. Pharmacists are creating tiered allocation systems: who gets the last vial of norepinephrine? The 72-year-old with septic shock? Or the 35-year-old with high blood pressure? These aren’t theoretical questions. They’re daily decisions. Some hospitals are stockpiling. Others are switching to oral versions when possible - like using pills instead of IV fluids for hydration. A few are building direct relationships with smaller, overseas suppliers. One hospital in Ohio started importing saline from a Canadian manufacturer after their U.S. source dried up. It cost more. It took longer. But it kept their ER running. The problem? These fixes take months to set up. A new pharmacy director needs, on average, six months just to learn how to manage shortages effectively. And only 45% of hospitals have written, updated protocols. The rest are winging it - which increases the risk of medication errors.The Human Cost

Behind every shortage is a patient. A child. An elder. Someone who needs a drug that doesn’t exist right now. Sixty-eight percent of hospital pharmacists say they’ve had to use a less effective alternative because the real drug wasn’t available. Forty-two percent say they’ve seen patient outcomes worsen as a result. One pharmacist on Reddit wrote: “Running out of normal saline for three weeks straight forced us to get creative with oral rehydration for post-op patients - never thought I’d see the day.” And then there’s the moral weight. More than two-thirds of pharmacists say they’ve faced ethical dilemmas during shortages. Who gets the last dose? Who gets put off? Who gets told, “We’re sorry, we don’t have it”? These aren’t decisions made in boardrooms. They’re made in quiet rooms at 2 a.m. by people who just want to help.

What’s Next?

The Biden administration pledged $1.2 billion to bring drug manufacturing back to the U.S. That sounds good. But experts say it will take 3 to 5 years to see any real impact. Meanwhile, the number of shortages hasn’t dropped meaningfully. It went from 270 in April 2025 to 226 in July - a small dip, but still far above historical norms. Only 12% of manufacturers use newer, more resilient technologies like continuous manufacturing - which could prevent batch failures and speed up production. Why? Because it’s expensive. And with profit margins this thin, no one wants to bet on it. Climate change is making things worse. Tornadoes, floods, wildfires - they’re no longer rare disruptions. They’re part of the new normal. And they hit manufacturing hubs hard. The truth? Without major policy changes - like guaranteed minimum profits for critical generics, mandatory domestic backup suppliers, or penalties for chronic underinvestment - this crisis will keep growing. And hospitals? They’ll keep being the ones left holding the bag.What Can Be Done?

It’s not hopeless - but it needs action. Here’s what actually helps:- **Financial incentives for manufacturers** to produce high-risk injectables, even if they’re not profitable

- **Diversifying global supply chains** - not just relying on China and India

- **Mandating stockpiles** of essential injectables at federal and state levels

- **Fast-tracking approvals** for alternative suppliers during shortages

- **Investing in domestic continuous manufacturing** - not just talking about it

Why are injectable drugs more likely to be in short supply than pills?

Injectable drugs require sterile, contamination-free manufacturing - a process that’s far more complex and expensive than making pills. Even small issues like a leaky air filter or a mislabeled batch can shut down production for months. They also have low profit margins, so manufacturers don’t invest in backup systems or extra capacity. Pills can be made in bulk, stored for years, and easily substituted. Injectables can’t.

Which patients are most affected by injectable shortages?

Elderly patients, especially those aged 65 to 85, are hit hardest. They’re more likely to be in hospitals, need chemotherapy, heart medications, or antibiotics via IV. Cancer patients, ICU patients, and those undergoing surgery are also at greatest risk. When anesthetic or vasopressor drugs run out, surgeries get canceled and lives are put on hold.

Can hospitals just order more from other countries?

It’s not that simple. Many injectables are made by just one or two global manufacturers. If the factory in India gets shut down by the FDA for quality issues, there’s no backup. Even if another country has the drug, U.S. regulations require FDA approval for each new supplier - a process that can take 12 to 18 months. During a shortage, that’s too slow.

Are there any alternatives to the drugs that are in short supply?

Sometimes, but not always. For fluids like saline, hospitals have used oral rehydration. For some antibiotics, they’ve switched to oral versions. But for drugs like epinephrine, norepinephrine, or chemotherapy agents, there are no safe or effective substitutes. Using the wrong drug can be deadly. That’s why pharmacists spend so much time getting approval from hospital committees before switching - even when lives are on the line.

Why hasn’t the FDA fixed this yet?

The FDA can’t force companies to make more of a drug. They can inspect, warn, or delay approval - but they can’t mandate production. Their tools are reactive, not preventive. Even with new laws requiring earlier notice of shortages, the agency lacks authority to fund factories, guarantee profits, or require backup suppliers. Without those powers, they’re trying to stop a flood with a bucket.

Write a comment