Smoking and Health Disparities Calculator

Enter Your Demographics

This tool estimates potential health impacts based on smoking prevalence and health outcomes by socio-economic status.

Estimated Health Impact

Based on your selections, here's what the data shows:

- Estimated smoking prevalence in this group.

- Projected chronic disease mortality rate.

- Average age of death: years.

Insight: Higher smoking rates correlate with significantly higher mortality and shorter lifespans in disadvantaged groups.

When you hear the word smoking you might think of lungs, coughs, and cancer. What’s less obvious is how tobacco use acts like a wrecking ball, tearing apart the health of already vulnerable groups and widening the gap between the well‑off and the disadvantaged.

Understanding Health Disparities

Health disparities are systematic differences in health outcomes that trace back to social, economic, and environmental disadvantages. They show up as higher rates of chronic disease, lower life expectancy, and reduced access to quality care among low‑income families, racial minorities, and Indigenous peoples. The root causes are not biology but the unequal distribution of resources, education, and power.

Smoking Patterns Across Populations

Smoking is a behavior that spreads unevenly. In Canada and the United States, national surveys consistently reveal that people living under the poverty line are 2‑3 times more likely to smoke daily than those with a college degree. Among Indigenous communities, smoking rates can exceed 40% in some regions, compared with the national average of around 14%.

- Low‑income adults: 26% daily smokers

- College‑educated adults: 7% daily smokers

- Black adults: 15% daily smokers

- Indigenous adults: 38% daily smokers

These numbers are not accidental; they reflect targeted marketing, higher stress levels, and limited access to cessation resources.

Why Smoking Deepens the Gap

The link between smoking and health disparities operates on three fronts:

- Biological toll: Each cigarette delivers toxins that accelerate heart disease, COPD, and many cancers. When a group already facing limited medical care picks up those toxins, the resulting disease burden is far heavier.

- Economic strain: Money spent on cigarettes reduces household budgets for nutritious food, housing, and education. A family that spends $150 a month on tobacco could instead afford healthier groceries or childcare.

- Access barriers: Low‑income neighborhoods often lack affordable cessation programs or pharmacies with nicotine‑replacement therapies. Even when programs exist, they may not be culturally tailored, leading to low uptake.

Case Studies: Who Feels the Pain Most?

Low‑income communities experience a double‑hit. In Vancouver’s Eastside, surveillance data from 2022 showed a 30% higher lung‑cancer mortality rate compared with affluent Westside districts, despite similar overall smoking rates. The difference stems from delayed diagnosis, fewer screening facilities, and higher exposure to other pollutants.

Indigenous populations face legacy issues. Colonial policies displaced many communities, creating chronic stress that fuels tobacco use as a coping mechanism. Coupled with under‑funded health clinics, this results in premature deaths-average life expectancy among First Nations in Canada is 7 years lower, with tobacco‑related disease accounting for a significant share.

Racial minorities also bear a disproportionate load. A 2023 CDC analysis linked higher smoking prevalence among Black adults to increased rates of stroke and hypertension, conditions already amplified by limited access to primary care.

Economic Consequences for Society

The fiscal impact is staggering. In 2024 the Canadian Institute for Health Information estimated that smoking‑related health costs exceeded CAD7billion, with low‑income households shouldering a larger share of out‑of‑pocket expenses. In the U.S., the CDC reported that tobacco‑related medical spending was over USD170billion in 2022, and more than half of those costs were concentrated in the lowest income quintile.

When a community spends a larger slice of its limited income on treating preventable diseases, resources for education, employment, and housing shrink-creating a vicious circle that perpetuates inequality.

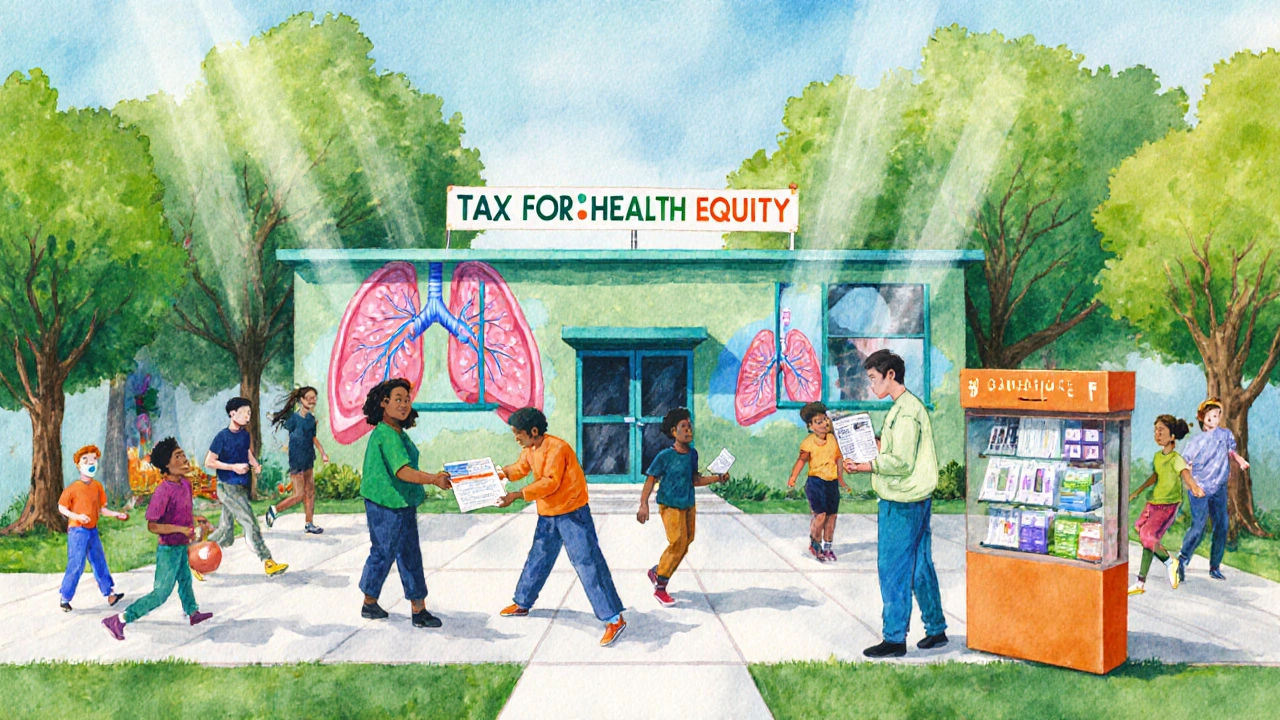

Policy Levers: How to Break the Cycle

Effective public‑health strategies must tackle both smoking itself and the social conditions that make it attractive.

- Taxation on cigarettes has consistently reduced consumption, especially among price‑sensitive low‑income smokers.

- Funding tobacco‑control measures such as plain packaging, smoke‑free public spaces, and rigorous advertising bans.

- Deploying culturally tailored cessation programs that incorporate community leaders, language support, and mobile‑health tools.

- Improving access to affordable nicotine‑replacement therapy through universal health coverage or low‑cost community pharmacies.

- Addressing underlying stressors-housing instability, food insecurity, and discrimination-through integrated social‑service models.

When these policies are rolled out together, they create a synergistic effect: higher prices deter initiation, while supportive services help current smokers quit, and broader social investments reduce the stress‑driven need to smoke.

Quick Checklist for Communities and Policymakers

- Assess local smoking prevalence by income, race, and age.

- Identify gaps in cessation services-especially in underserved neighborhoods.

- Implement higher excise taxes earmarked for health‑equity programs.

- Partner with Indigenous and community‑based organizations to co‑design culturally relevant quit‑help resources.

- Track health‑outcome metrics (e.g., COPD hospitalizations) pre‑ and post‑intervention.

- Allocate funding for affordable housing and food assistance alongside tobacco‑control measures.

Comparison of Smoking Prevalence and Health Outcomes by Socio‑Economic Status (2023)

| Income Quintile | Smoking Prevalence | Cardiovascular Mortality | Respiratory Mortality | Average Age of Death (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowest 20% | 28% | 210 | 180 | 68 |

| Second 20% | 22% | 150 | 130 | 72 |

| Middle 20% | 15% | 110 | 95 | 78 |

| Fourth 20% | 10% | 80 | 65 | 82 |

| Highest 20% | 6% | 50 | 40 | 86 |

The table makes it clear: higher smoking rates in poorer groups translate directly into higher mortality and a shorter lifespan.

Moving Forward: A Vision for Health Equity

Imagine a future where a teenager in a low‑income neighborhood never feels the social pressure to pick up a cigarette because schools, community centers, and health clinics all provide supportive environments. Achieving that vision requires a coordinated effort: stronger taxes, better-funded cessation services, and policies that lift families out of poverty.

By treating smoking not just as an individual choice but as a catalyst for health inequality, governments and community leaders can make a decisive strike against the widening gap.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do low‑income people smoke more?

Stress, targeted advertising, and limited access to affordable cessation tools create a perfect storm. When disposable income is scarce, a cheap, legal product like cigarettes becomes an accessible coping mechanism.

Can higher taxes really help?

Yes. Studies from Canada, the U.S., and Europe show that a 10% price increase cuts overall consumption by about 4%, with an even larger drop among low‑income smokers who are most price‑sensitive.

What community‑based programs work best?

Programs that combine culturally relevant messaging, peer support, and free nicotine‑replacement therapy see quit rates 2‑3 times higher than generic campaigns. In British Columbia, the "First Nations Smoke‑Free Initiative" cut smoking rates by 12% over three years.

How does smoking affect COVID‑19 outcomes for disadvantaged groups?

Smokers are more likely to develop severe COVID‑19, and low‑income communities-already hit harder by the pandemic-saw higher hospitalization rates. The combined effect magnifies existing health gaps.

What role can employers play?

Workplace wellness programs that offer free counseling, nicotine patches, and flexible schedules for medical appointments have been shown to reduce smoking prevalence among blue‑collar workers by up to 15%.

Write a comment